Critical Reflection

In Unit 1, I discussed how my paintings aim to challenge reductive narratives by emphasizing individuality and authenticity of Chinese women’s diasporic experience, shaped by colonial legacies and contemporary displacement in the UK. My intention is to reclaim authorship and critically explore the representation of Chinese diasporic women through a personal and historical grounded lens. I concluded with a question regarding stereotypes and an aspiration to locate the nuances of the mis-portrayals. Building on this foundation, in Unit 2, I started to explore these themes more intimately through my own lived experience and depicting them on my paintings as an autobiography through self-portraiture.

“The self-portrait and the I/Eye”

Partou (2004, pp.96-114)

British-Iranian artist and writer Partou Zia reflects on the self-portrait as a genre that offers a space to express a self in motion, one seeks recognition rather than simply accepting a “likeness”, even though it draws on the traditional mirror reflection (Partou, 2004, p.98). In many of her paintings, such as 40 Nights and 40 Days (2008) (see figure 1), the depiction of herself is deliberately unrealistic. She illustrated herself in grey skin tone, using a loose, painterly approach rather than focusing on details. Zia also remarked that “autobiography through self-portraiture is a rewriting of histories” (ibid.). Highlighting the self-portrait as a tool to reclaim authorship.

This notion resonates with my own painting Pictorial Journal #1: Hypervigilance (2025), where I intentionally resist depicting my appearance. Instead, I show only a side profile, fully obscured by a hat and my hair. This choice of depiction reflects my desire to retain authorship over my narrative, rather than drawing on visual likeness. The gesture of turning my face away becomes a reflection of an act of protection, based on my personal experiences of being verbally assaulted, as a non-British woman in the UK public spaces.

American artist Amy Sherald’s painting A Midsummer Afternoon Dream (2020) (see figure 2) refers to the theme of mistaken identity from William Shakespeare’s comedy and misplaced affection (Karnes, 2022, p.70). This painting depicts a Black woman wearing a flowy azure dress, leaning against a pastel-yellow bicycle, in a serene, summery setting. Despite the vibrant backdrop, the sitter’s skin tone is depicted in a monochromatic grey, a decision she explains as a way to de-emphasise racial coding and shift focus on a sense of familiarity (ibid.). She explains that Blackness has been "codified to represent resistance" (ibid.), this idea is echoed by Stuart Hall, who also observes that “Biological racism privileges markers like skin colour. But those signifiers have always also been used, by discursive extension, to connote social and cultural differences.” (Hall and Morley, 2019, p.110)) Sherald’s approach aims to undo this notion.

I believe Sherald’s concern on racial coding and representation resonate with how Chinese, and even more broadly, Asian people, are often perceived within western societies. The rise of anti-Asian hates or Sinophobia reinforces how racialised bodies intertwined with vulnerability. Having lived in the UK as a woman of a minority group for several years, I have personally encountered public verbal harassment, which further informs my decision to obscure my face and dress in loose coat, wearing a hat in the painting. This approach reflects on my caution negotiating public space. The ambivalent depiction reflects the desire of safety and protection in the paintings.

More importantly, I believe the concern of safety is a shared experience by women in the world. By depicting myself under a concealing outfit, I seek to address not only the diasporic identity, but also how I navigate public space in a vulnerable body. My paintings reflect on how I choose to be seen or remain unseen.

Reference:

Bao, H. (2022) ‘The New Generation: Contemporary Chinese Art in the Diaspora’, Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, 9(1), pp. 3–17. doi:10.1386/jcca_00053_2.

Galleries Now (2025) A midsummer afternoon dream, GalleriesNow.net. Available at: https://www.galleriesnow.net/artwork/a-midsummer-afternoon-dream (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Hall, S. and Morley, D. (2019) Essential Essays. volume 2, Identity and diaspora. Durham: Duke University Press.

Karnes, A. (2022) Women painting women. Fort Worth, TX, New York, NY: Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth ; DelMonico Books, ARTBOOK/D.A.P.

Partou (2004) ‘5’, in The self-portrait and the I/eye. London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, pp. 96–114.

Sherald, A. (no date) A midsummer afternoon dream, GalleriesNow.net. Available at: https://www.galleriesnow.net/artwork/a-midsummer-afternoon-dream (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Tate (2008) ‘40 nights and 40 Days’, Partou Zia, 2008, Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/zia-40-nights-and-40-days-t15995 (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

*Full bibliography is available at the end of the page.

Figure 1. 40 Nights and 40 Days (2008) Oil paint on canvas, 153x183x5.2cm (Tate, 2008)

Figure 2. A Midsummer Afternoon Dream (2020) Oil on canvas, 269.2x256.6x6.4cm (Gallerier Now, 2025)

Landscape, Race and National Identity:

The Photography of Ingrid Pollard

Pil Kinsman (1995, pp.300-310)

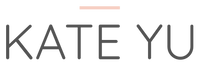

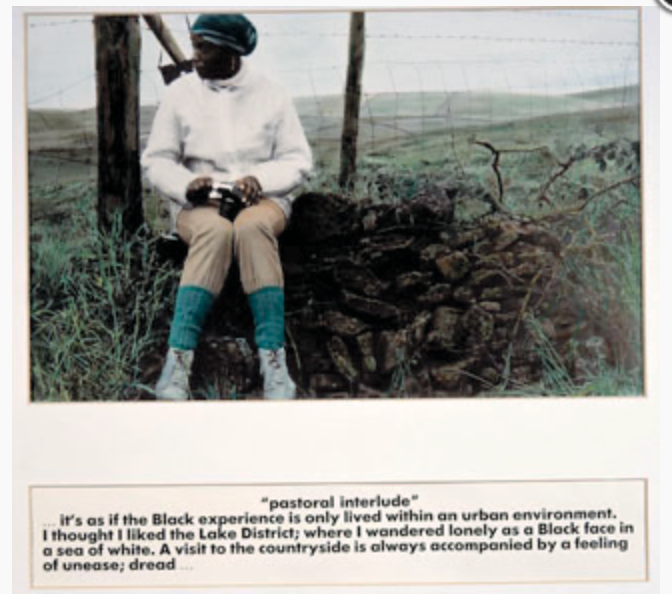

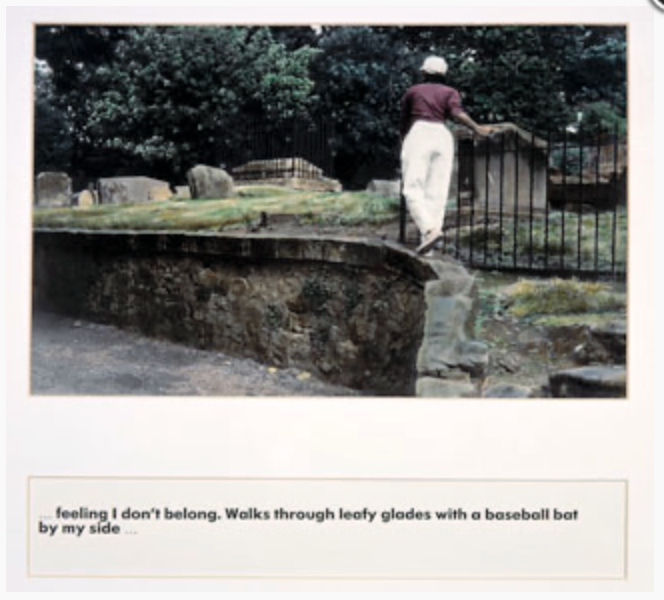

British artist and photographer Ingrid Pollard in her exhibition Pastoral Interlude (1984) showcased a series of five tinted photographs depicting five black figures situated in British rural landscapes (see figure 3). Each image is paired with text expressing feelings of unease, alienation and displacement experienced by black individuals in the British countryside (Kinsman, 1995, pp.301-302). Kinsman quoted Stephen Daniels that “the power of landscapes as signifiers of national identity (ibid.), asserting that “if a group is excluded from these landscapes of national identity, then they are excluded to a large degree from the nation itself (ibid.).

Pollard’s Pastoral Interlude (1984) was inspired by her personal holiday experiences. However, her visits to the British countryside evoked a deep sense of unease, feelings of not belonging, the threat of violence or even death, and of the history of slavery that brought black people to Britain (ibid.). While I do not personally associate the British countryside with violent history, I nevertheless experience a sense of wrongness, discomfort and displacement. The countryside’s noble and historical association makes me feel inaccessible or alienating, hinting exclusion.

For instance, a few years ago, I attended tennis matches at Wimbledon. Aware of tournament’s strict all-white dress code for the players, an enduring rule from the Victorian era, I deliberately chose to wear a white cotton dress in an attempt to blend in. Yet, instead of feeling included, I felt more alienated. I began to question they symbol of white, wondering if the white suggests cleanliness, modesty? If so, what does it mean for colours beyond white? Are they consider unclean or improper?

Bhabha highlights how identity in contemporary has moved beyond simple classifications such as class or gender, and instead emphasizing intersecting subject position such as race, gender and location. (Bhabha, 2012, p.2) My experience at Wimbledon gave me a subtle and unsettling sense of white supremacy embedded in aesthetic façade, reinforcing my sense of displacement and exclusion. In response, I added multiple colours on the white dress in the painting, not only to illustrate the fabric’s folds, but as an act of subtle protest against the dated cultural norms, advocating for a more inclusive, modern identity.

As Bhabha articulates, these “in-between” spaces provide the terrain for exploring selfhood, both individual and collective. (ibid.) “[it] initiate new signs of identity, and innovative sites of collaboration, and contestation, in the act of defining the idea of society itself” (ibid.) In my ongoing practice, these “in-between” spaces offer opportunities to express my personal narratives of displacement and belonging.

None the less, Karnes noted, “ Selfhood is explored through representation of the self or a single identity and through representations of the collective woman.” In order to get a better understanding, in unit 3, I aspired to check out archive from the women’s library, get to learn more from women in Chinese community in the UK.

Reference:

Ahmed, S. et al. (2020) Uprootings. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Bhabha, H.K. (2012) The location of culture. Routledge.

Pollard, I. (2021) Pastoral interlude, ingrid pollard photography. Available at: http://www.ingridpollard.com/pastoral-interlude.html (Accessed: 15 May 2025

Kinsman, P. (1995) ‘Landscape, Race and National Identity: The Photography of Ingrid Pollard’, Area, 27(4), pp. 300–310. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20003600?casa_token=wBCuFuVSuBMAAAAA%3AL75udUjg7uo2J5b9Ez1Q3NmrGiL-ZVjk8QUnbksiVbiIaO6UgQqYmYZEsxpDF-dv6b0Pw3PMxRaX4X-EaBKQQb_5_5pxq_4X1SfsyKLsc1PQzDi9zw&seq=1 (Accessed: 2025).

*Full bibliography is available at the end of the page.

Figure 3. Pastoral Interlude (1988), Hand tinted silver print 5 50.8x61cm (Pollard, 2021)

“Performing Fortune Cookie”

Richie Neil Hao

Previously in Unit 1, I noted how artists like Hung Liu and Paula Rego often incorporated cultural motifs and metaphorical symbols into their paintings and how in contrast, I have often struggled to find tangible items or symbols that authentically represent my identity in my painting. This tension resonates with Stuart Hall’s insight that “identities are about questions of using the resources of history, language and culture in the process of becoming rather than being: not ‘who we are’ or ‘where we came from,’ so much as what we might become, how we have been represented and how that bears on how we might represent ourselves” (1996, p.4). I am convinced by Hall and believe that identity cannot be reduced to a single fixed emblem, and it is the matter of how we choose to portray ourselves. Therefore, I am moving away from finding an object to represent selfhood but to through one object as a vehicle/vessel to get a better understanding of my identity.

Origin

Fortune cookies -- a small, crisp, folded crescent shaped cookie with a hollow interior that holds a slip of paper containing a fortune message – are often synonymous with Chinese restaurants and Chinatown, yet their origin remains a mystery. There are numerous versions of the origin surround this invention. Some credit David Jung, a Chinese immigrant and founder of the Hong Kong Noodle Company in Los Angeles before World War 1, as the inventor (Hao, 2020, p__). Others argue that the cookies originated in Japan. Researcher Yasuko Nakamachi presents evidence that fortune cookies originated in Kyoto, Japan (Lee, 2008); Still others suggest that the cookies were introduced and popularized by Japanese-American families in San Francisco and Los Angeles (Lee, 2008). Some said during World War 2, Chinese-American bakeries owner took over Japanese businesses and contributed to their Chinese restaurants.

As Homi K. Bhabha noted the “origin” itself is not stable or real and “the masking and splitting of ‘official’ and phantasmatic knowledges to construct the positionalities and oppositionalities of racist discourse” (2012, p.117) He continues, “Stereotyping … is a much more ambivalent text of projection and introjection” (ibid) I believe this is why Hao criticies and challenges Scarup’s argument on identity that “there is an assumption that [identity] has to be coherent, unified, [and] fixed” (Hao, 2020, p.__ citing Sarup, 1996, p.14). Perhaps we can avoid stereotyping by not urging to get one fixed origin.

The mysterious background of fortune cookies is already fascinating in itself, revealing how this little piece of cookies contains so much uncertainty and ambiguity which I am resonate with as one who has often being generalised in one single identity.

Contemporary representation

Liu and Korean-American artist Jiha Moon, both use fortune cookies in their artworks but they do so with different intentions, materials and conceptual frameworks hence with distinct approaches.

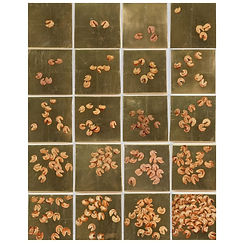

Liu’s installation Jiu Jin Shan (Old Gold mountain) (1994) (see figure 4) is an installation with pile of over two hundred thousand fortune cookies forming a symbolic gold mountain that floods over intersecting railroad beneath (e-flux education, 2013). The work commemorates the history of the Chinese laborers who built the railroads to support the West Coast Gold Rush, while evoking the hope shared among these immigrants (ibid.). As art critic Ester Barkai commented, “she continued to use the theme of fortune cookies as a medium and metaphor for cultural experience in Jiu Jin Shan” (Artswatch, 2022), hence multiple mixed media works Fortune Cookies (2013) (see figure 5).

In contrast, Moon’s fortune cookies are sculpted from hand-folded porcelain. Her intention is to challenge the idea of a static cultural identity (Artspace Editors, 2018), and to explore the misidentification of the fortune cookies and hybridity. Her cookies are bold, colourful, often hand-painted with motifs blending folk symbolism such as Asian landscape, pop culture like Angry Birds. Through this visual, Moon critically challenge East/West syncretism, hybridity and the generalised Asian-American identity (ibid.).

Inspired by both Liu and Moon, my intention of making artworks in the theme of fortune cookies is not to generalise or stereotype, nor to use them as metaphor for identity. Rather, I aim to reappropriate the cookies as a culturally loaded object, one that allows me to explore and point out the fluidity, ambiguity and evolving nature of diasporic identity through both paintings and sculptures.

Reference:

Ang, I. (2001) On Not Speaking Chinese : Living Between Asia and the West. London: London Routledge.

ArtsWatch, O. and Barkai, E. (2022) Remembering Hung Liu at JSMA • Oregon ArtsWatch, Oregon ArtsWatch • Arts & Culture News. Available at: https://www.orartswatch.org/remembering-hung-liu-at-jsma/ (Accessed: 20 May 2025).

Artsy (2025) Jiha Moon - artworks for sale & more | artsy, Artsy. Available at: https://www.artsy.net/artist/jiha-moon (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Bhabha, H.K. (2012) The location of culture. Routledge.

CONTAINER (2013) Hung Liu, Fortune Cookie, 2013, CONTAINER. Available at: https://www.containertc.org/artists/39-hung-liu/works/229-hung-liu-fortune-cookie-2013/ (Accessed: 10 May 2025).

e-flux (2013) Hung Liu: Offerings - e-flux education, e-flux education. Available at: https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/108886/hung-liu-offerings/ (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Hung, D.J. (2025) I am not a tourist. S.l.: HarperCollins Publishers.

Lee, J. 8. (2008) The fortune cookie’s origin: Solving a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside a cookie (published 2008), The fortune cookie’s origin: Solving a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside a cookie. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/16/travel/16iht-fortune.9260526.html (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Wei, L. (2025) Jiha Moon Essay: Bio, Displacements. Available at: https://displacements.org/artists/jiha-moon/ (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

*Full bibliography is available at the end of the page.

Figure 4. Jiu Jin Shan(1994), 200,000 fortune cookies with support structure and train tracks. Dimensions variable (e-flux, 2013)

Figure 5. Hung Liu, Fortune Cookie (2013), mixed media on panel, set of 20, 25.4x25.4cm (Container, 2013)

Figure 6. Jiha Moon, YouandI (Blue), (2019) Porcelain, underglaze, glaze

12.1 × 13.3 × 14 cm (artsy, 2025)

Bibliography

Ahmed, S. et al. (2020) Uprootings. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Ang, I. (2001) On Not Speaking Chinese : Living Between Asia and the West. London: London Routledge.

ArtsWatch, O. and Barkai, E. (2022) Remembering Hung Liu at JSMA • Oregon ArtsWatch, Oregon ArtsWatch • Arts & Culture News. Available at: https://www.orartswatch.org/remembering-hung-liu-at-jsma/ (Accessed: 20 May 2025).

Artsy (2025) Jiha Moon - artworks for sale & more | artsy, Artsy. Available at: https://www.artsy.net/artist/jiha-moon (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Bao, H. (2022) ‘The New Generation: Contemporary Chinese Art in the Diaspora’, Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art, 9(1), pp. 3–17. doi:10.1386/jcca_00053_2.

Bhabha, H.K. (2012) The location of culture. Routledge.

Braithwaite, P. (2025) ‘An unflinching eye: Claudette Johnson in conversation’, Wasafiri, 40(1), pp. 83–95. doi:10.1080/02690055.2025.2435165.

CONTAINER (2013) Hung Liu, Fortune Cookie, 2013, CONTAINER. Available at: https://www.containertc.org/artists/39-hung-liu/works/229-hung-liu-fortune-cookie-2013/ (Accessed: 10 May 2025).

e-flux (2013) Hung Liu: Offerings - e-flux education, e-flux education. Available at: https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/108886/hung-liu-offerings/ (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Galleries Now (2025) A midsummer afternoon dream, GalleriesNow.net. Available at: https://www.galleriesnow.net/artwork/a-midsummer-afternoon-dream (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Hall, S. and Morley, D. (2019) Essential Essays. volume 2, Identity and diaspora. Durham: Duke University Press.

Hung, D.J. (2025) I am not a tourist. S.l.: HarperCollins Publishers.

Karnes, A. (2022) Women painting women. Fort Worth, TX, New York, NY: Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth ; DelMonico Books, ARTBOOK/D.A.P.

Kinsman, P. (1995) ‘Landscape, Race and National Identity: The Photography of Ingrid Pollard’, Area, 27(4), pp. 300–310. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20003600?casa_token=wBCuFuVSuBMAAAAA%3AL75udUjg7uo2J5b9Ez1Q3NmrGiL-ZVjk8QUnbksiVbiIaO6UgQqYmYZEsxpDF-dv6b0Pw3PMxRaX4X-EaBKQQb_5_5pxq_4X1SfsyKLsc1PQzDi9zw&seq=1 (Accessed: 2025).

Lee, J. 8. (2008) The fortune cookie’s origin: Solving a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside a cookie (published 2008), The fortune cookie’s origin: Solving a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside a cookie. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/16/travel/16iht-fortune.9260526.html (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Partou (2004) ‘5’, in The self-portrait and the I/eye. London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, pp. 96–114.

Pollard, I. (2021) Pastoral interlude, ingrid pollard photography. Available at: http://www.ingridpollard.com/pastoral-interlude.html (Accessed: 15 May 2025

Sherald, A. (no date) A midsummer afternoon dream, GalleriesNow.net. Available at: https://www.galleriesnow.net/artwork/a-midsummer-afternoon-dream (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Tate (2008) ‘40 nights and 40 Days’, Partou Zia, 2008, Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/zia-40-nights-and-40-days-t15995 (Accessed: 15 May 2025).

Tate (2005) Marlene Dumas. Jen. 2005 | moma, Tate. Available at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/102421 (Accessed: 19 May 2025).

Wei, L. (2025) Jiha Moon Essay: Bio, Displacements. Available at: https://displacements.org/artists/jiha-moon/ (Accessed: 15 May 2025).