Critical Refection

My practice began as a form of critical autobiography, using painting to reflect on my experience of migration from Hong Kong to the UK. In the earlier stages, inspired by Anselm Kiefer’s Innenraum (1981), I became interested in how institutional spaces embody power and national narratives and how the self is situated within these structures. I positioned myself directly as the subject within architectural spaces that were shaped by imperial legacies, to help myself understand my identity and belonging in relation to colonial history and cultural memory.

Over time, my focus shifted. The subject moved from myself to my cat, as a living companion, whose perspective allowed me to rediscover joy, connection, and belonging. I examine how shifting towards a relational subject allows my practice to approach intimate and emotionally grounded belonging.

These reflections trace the transformation into two phases. In Phase One, I explore how institutional and historical spaces can shape my sense of self through autobiographical paintings. In Phase Two, I examine the shifting of subject toward my cat, which allows me to re-examine and transform. Together these two phases not only map what I paint but show how my emotions have changed through the act of painting.

Research methodology

My methodology draws on Barbara Howey’s notion of critical autobiography (2009), using personal experience as a lens for reflection. Following Morwenna Griffiths’ understanding of the self (2003) and Michel Foucault’s Technology of the self (1982), I explore how identity and belonging can be shaped by memory, emotion and self-care. Influenced by John Berger’s Why Look at Animals? (2000), I approach the figure of my cat as both co-subject and metaphor, a way to look outward and inward simultaneously. Donna Haraway’s The Companion Species Manifesto (2020) further informs this relationship, framing the companionship as a process of becoming. The act of painting operates as a process of self-examination and transformation.

Phase One:

Locating the self and belonging within colonial structures

As Alison Hirst and Michael Humphreys argue, 'Place is defined as ‘a meaningful segment of space’ (Cresswell, 2012: 280) distinguished by its specific location, material form, and the subjective meanings, individual or shared, that are attributed to it.' (Hirst & Humphrey, 2020, p.6). In this sense, institutional spaces are not merely a physical location but have meanings in them. This meaning also actively shapes how individuals understand themselves and how they position in relation to history.

To reflect on how colonial history shapes my identity and belonging, I painted Pictorial Journal #3: Under the Shadow of Colonialism (2025) and Pictorial Journal #4: Invisible (2025) both situate the self within institutional space, interrogating my comprehension of identity within the power hidden behind historical architectural environments.

In Pictorial Journal #3, I depict myself standing at the base of a grand staircase in Weston Hall of the British Museum, a neo-classicism architecture building built in 1845 (British Museum, 2025). It was built in the same era that the Treaty of Nanjing made Hong Kong a British colony (Britannica Editors, 2025). Although it has been over a hundred years since the Treaty of Nanjing was signed, this Greco-Roman-inspired architecture inside Weston Hall to me evokes a sense of imperial authority and cultural hierarchy.

This portrayal references Anslem Kiefer’s Innenraum (1982) (see figure 1), a depiction of a vast, empty architectural space based on Albert Speer’s Reich Chancellery in Berlin where Hitler would meet with his military staff. It is to Kiefer a collective memory of trauma and guilt. (Schjeldahl, 2023) Like Innenraum (1981), Pictorial Journal #3 depicts through the one point perspective in the painting, the bruised violet tone and the heavy grided ceiling, creating an atmosphere of oppressive grandeur and eerie stillness.

Figure 1, Anselm Kiefer, Innenraum (Interior), 1981, watercolour, 24.13 x 25.9cm (Schjeldahl, 2023)

Figure 2,

Anselm Kiefer, Innenraum (Interior space), 1982, oil, acrylic, shellac, and emulsion on canvas, deminsion unknown

Different from Kiefer’s depiction of solely interior space, Pictorial Journal #3 included an illustration of myself as a subject. I depicted myself positioning at the base of the grand staircase, glazing up toward the surrounding neoclassical sculptures and imperial architecture illuminated by a skylight. The composition is dominated by deep purples, muted blues and soft yellows, positioning my figure as the protagonist and the statues as antagonists, creating a quiet yet tense atmosphere. The painting stages my body in direct relation to the architecture of the empire, asks about my position in this colonial history.

While Pictorial Journal #3 depicts a historical interior scene, Pictorial Journal #4, in contrast, depicts an outdoor scene dominated by a huge structure in the background reminiscent of Windsor Castle. The tower is painted in a golden undertone with a purple hue as a metaphor of affluence. The golden tone speaks for itself suggests opulence. For the purple tone, according to James Fox, "Purple’s natural scarcity forced people to develop ingenious and elaborate manufacturing methods, lending the resulting colourants an aura of mystery and luxury (2023, p.169). In front of the building stands a bronze statue of Queen Victoria covered in a deep green tone, strikingly contrasting with the warm and luminous background. Similar to Pictorial Journal #3, I include an illustration of myself situated at the base of the painting. However, instead of standing, this time I outlined myself in a huddled position by using white paint with an intentionally unfinished depiction, evokes the feeling of being left out.

The depiction of the staircase in Pictorial Journal #3 occupies a relatively huge proportion of the canvas, becoming a dominant visual and conceptual element. And instead of painting it in photo-realistic detail, I painted the steps in alternating strips of light and dark with economical brushstrokes. This approach is an allusion to Caroline Walker’s treatment of everyday objects in her works such as Frying (2024), where she depicts stacked plates in alternating brushstrokes. The plates are stored beneath a kitchen table as they act as an indicator of the role of the working-class woman), carrying the weight of narrative significance. Through this modest depiction of the plates, Walker subtly signals labour and class in the domestic scene.

Left: Figure 4,

Detail shot from Pictorial Journal #3

Right: Figure 5,

Detail shot from Frying

Figure 3,

Caroline Walker, Frying, 2024, oil on canvas, dimension

Similarly, in my painting, a staircase functions as a structural metaphor. It is not simply a setting but a symbol that suggests power, hierarchy and historical authority. The steep staircase invites viewer’s eye to climb. The upward perspective recreates the embodied experience of standing there and looking up. This perspectival pull is essential as I am not merely showcasing a place but recreating the sensation of being positioned within it.

The staircase’s prominence is intended to highlight the question of power that persists. It is a key context of this painting. I reckon Kiefer’s uses of multimedia to create a dense, almost sculptural surface. He scraped and layered paint onto the canvas, mimicking the decay of marble and the ruin. These materials created a non-smooth surface, holding a sense of weight that represents a metaphor for the burden of cultural memory and emotional weight.

Although my own painting is not as heavily textured, the painted surface with the cool violet tones carries emotional temperature. Purple here is associated with imperial authority, as James Fox notes, “…colour was renamed ‘imperial’ or ‘royal purple’ and became an exclusive symbol of the emperor” (Fox, 2023, p.171). And emotional ambivalence allowing the work to question: how does colonial history remain present in my sense of self? As Griffiths argues, the process of self-understanding requires continually returning to the questions of “who or what am I?” and “how have I been shaped”, what one can do about it? (1995, p.75).

Scale also plays an important role in paintings. While Kiefer’s monumental canvases engulf the viewer, my format of 100cm x 120cm, offers presence without domination. Displayed at eye level, the painting’s muted purple and contrast draw attention, inviting them to feel the spatial and asserting the seriousness of its subject while maintaining a contemplative stillness.

In both Pictorial Journal #3 and #4, institutional spaces serve as more than architectural backdrops. They are not solely about recognising structures of power, but become sites of negotiation where identity is tested against the lingering presence of colonial history and systems of privilege. These paintings uncover tensions such as seeing and yet remaining unseen, to be present yet marginal.

While these institutional spaces allowed me to confront how colonial history continues to shape my sense of self, the repeated act of locating myself within such contexts became emotionally heavy. This led me to seek another way of understanding belonging, which is grounded not in colonial power but in everyday companionship.

Left: National Gallery

Right: Weston Hall

Phase Two:

Shifting Subject - From Self to Cat

My practice has been heavily influenced by feminist perspective thinkers such as Griffiths, encouraging me to keep discovering self and identity (1995). Yet over time, this constant confrontation of structures of power and self-reflection led to emotionally exhausting gradually leading to burnout.

Foucault’s concept Technologies of the self (1988) provided a useful framework for a transition. Foucault describes how transformation can emerge through voluntary and reflective practices that enable one to understand, govern and reshape the self (1982, p.19). As Foucault explains, the concept was constituted in Greek as “επιμελεισθαι σεαυτου/ epimelesthai sautou”, translateed as the care of the self is a crucial part of philosophical practice (ibid.). This transaction helped me rethink the balance.

Left: Figure 6

Michael Ajerman

Reposto III; Reposto II; Reposto V

Medium and size unknown

(Arjerman, 2025)

Right: Figure 7

Michael Ajerman, Can’t You Hear Me Knocking, 2024-5

Medium and size unknown

(Arjerman 2025)

In the painter's forum, I asked Michael Arjerman a question about the reasons he paints cats. He said it all began with a loss of his close friend. In another interview conducted by Dale Berning Sawa, Arjerman mentioned that David Hockney created Dog Days (1993) series when he was having a huge crisis that many of his friends were ill and dying (Sawa, 2025). Painting of pets has become their language of reflection and healing. Therefore, over the summer, I spent time with my cat, trying to reconnect with the grounding joys I have experienced and experiencing. I started to do life sketches to seek a gentler and more joyful way of practice as an act of self-transformation.

Figure 8

David Hockney

Dog Days, 1993 (de Souza, 2024)

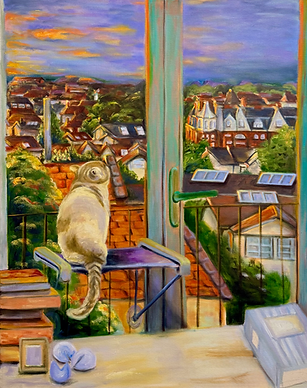

The shift in my mindset led me naturally toward painting my cat as the main subject. My cat AuAu, who is now thirteen and migrated with me from Hong Kong to the UK few years ago, has always been a companion throughout my life in the UK. He is not simply a subject of pet but a companion in resolving our sense of belonging in a foreign land. Observing his stillness and curiosity became a way of re-engaging with my surroundings. This change aligns with Haraways’s The Companion Species Manifesto (2003). She mentions the idea of companion species where relationships between humans and animals become spaces of connection and co-formation (Haraway, 2020, p.16). Through my cat’s perspective, I reconnect with the beauty and excitement of being in the UK including the history, architecture, surroundings, and domestic intimacy that are happening in my everyday life here.

“The pet offers its owner a mirror to a part that is otherwise never reflected."

Berger, 2009, P.13”

Also, in my mini-series Home is wherever I’m with you (2025), the focused depiction of part of me and my cat’s bodies resting against each other on the coach embodies themes of intimacy, vulnerability and mutual care. This aligns with Nicole Eisenman’s painting titled Close to the edges (2015) (see figure 9). It is an oil painting that depicts a figure and their feline companion lying against each other and peacefully falling asleep together (Sothebys Editor, 2025). Inspired by Eisenman, my triptych captures a quiet moment of rest. This depiction also becomes a metaphor for emotional interdependence, a safe space for both of us, a mutual understanding through closeness rather than isolation.

Through these paintings, my practice moves from critique toward connection. The shift of subject is not an escape but an expansion. It is a recognition that the self is not only shaped by history and institutions but also by the living relationships that sustain us.

Figure 9

Nicole Eisenman

Close to the Edge signed, 2015

oil on canvas

208.3x165.1cm

(Sothebys Editor, 2025)

Cat as a metaphor:

Why look at animals?

As Berger writes in Why Look at Animals?, "Animals are born, are sentient and are mortal. In these things they resemble man" (Berger, 2000, p.2). This recognition of shared sentience forms the basis of emotional and ethical connection between human and animals. It is not uncommand for artists to explore as a mirror for human consciousness. Recent research conducted by Kristyn R. Vitale*, Alexandra C. Behnke, and Monique A.R. Udell further supports this view. They suggest that cats may in fact bond with their owners like a child bonds with their parents. (Vitale et al., 2019) Such finding indicates that human-cat relationship is psychologically complex and meaningful, not incidental. For this reason, painting my cat is not merely a motif in my artwork but also a metaphorical extension of my emotional and psychological state, reflecting on the states of our belonging and individuality.

Cat as a co-subject:

The cat also functions as a co-subject in my paintings. The idea of the cat as a co-subject in my work draws on Jakob von Uexkull’s concept of Umwelt (Uexkull, 2013)[1], which proposes that every living being inhabits its own perceptual world. Uexkull illustrates this through the example of tick, which orient itself through a few cital cues including body heat and the smell of butyric acid, demonstrating that each species engages the world according to its own sensory needs and survival instinct (Uexkull, 2013, p.45). Similarly, through years of living with cats, I have observed that my cat’s umwelt is shaped by texture, movement, warmth in domestic environment. He has his own umwelt, emotion and perceptual life just distinct from and yet overlapping with my own.

[1]: Umwelt: Uexkull argues animals, including humans, do not live in the same objective world. Instead, each species perceives and engages with its environment through its own sensory and meaningful world – its Umwelt to survive. (von Uexkull, 2013, p. 5)

Depicting him in my paintings therefore acknowledges two perceptual worlds inhabiting the same space. This could be my interpretation of his perception or it may be my own emotional state projected onto him. My paintings becomes a space where these perspectives touch.

Pierre Bonnard frequently included cats in his painting, not merely as companions or motifs, but also as autonomous subjects that challenge anthropocentrism. For instance, In his painting Le Chat Blanc (1894) (see figure 10), the cat arches its body, looking at the viewer with cunning expression suggests the cats possess their own agency. Meanwhile, Woman with a Cat, or The Demanding Cat (1912) (see figure 11), the depiction of a lady and a cat sharing lunch together in the dining table shows connection between two different species in the same space.

Figure 10

Pierre Bonnard

Le Chat Blanc, 1894

oil on canvas

51.9 33.5cm

(Artsy, 2025)

Figure 11

Pierre Bonnard

Woman with a cat 1912

oil on canvas

78x77.5cm

(Artsy, 2025)

Inspired by Bonnard’s sensitivity and Haraway’s theoretical framework, my painting Pictorial Journal #5: Longing (2025), depicts my cat sitting on his hammock by the window, gazing out toward the sunset over the neighbourhood. At first glance, this depiction can be seen as him simply being a cat, enjoying the warm sunlight, admiring of the brilliant glow of the warm summer sunset shinning on the Victorian rooftops, from a cosy domestic setting. But the angle of his head tiled upwards appears like he is longing for something. This motion uncover a intertwine of contemplation and belonging, I am trying to depict the evolution from not just cat being a cat, but also lead me to reflect on belonging and rediscover the treasure to us in this foreign landscape.

Colour, Light, and Emotional Transformation

The shift in subject also brought a transformation in how I approached colour and light. My earlier paintings employed a muted, cool tone palette, evoking restraint, introspection and emotional weight of historical consciousness. These tones acted as a metaphor of the uncertainty of migration and adjustment.

As my emotional state changed, my palette expanded, embracing impressionist influences and my observation on British domestic spaces. The use of warmer and more luminous tones reflects a growing sense of comfort and attachment.

The transformation of my mindset through a different ways of seeing has significantly shaped how I dealing with emotion in my practice. As Vien Cheung notes, “We are surrounded by colour, but its significance in our lives goes far beyond simple aesthetic impressions. It has practical applications that help us navigate our environment. It can affect our mood” (Cheung, 2021). This understanding resonates with my own experience. Through the act of painting of my cat in domestic scenes, I began to explore how atmosphere and light could communicate internal states of belonging, curiosity and care.

In an article posted on ARTWalkway, “This isn’t just about how your eyes perceive light—it’s about how light stirs something inside you, something almost primal. As the sun warms your skin, your color [sic] choices follow suit. Your psyche absorbs the warmth, and your creative instincts respond to it" (ARTWalkway, 2024).

By slowing down and spending time observing and admiring my neighbourhood, my colour palette evolved from earlier muted tones toward a richer and higher saturation palette, reflecting a growing sense of comfort and attachment to place. In response to ARTWalkway's article, I reflected the sunset I observed in Pictorial Journal #5: Longing. The orange warm rooftops and the golden reflection evoking not just a physical warmth from the sunset but an inner warmth from my emotion. According to colour psychology, the orange tone “is friendly, warming and genuine”(Perryman, 2021, p.36) which was also align with my mood when I was creating this painting. The golden light across the Victorian rooftops becomes a metaphor for reconnection and peace, suggesting the light can act as a medium of emotional transformation.

Conclusion

My practice has allowed me to recognise my practice as a continual negotiation of selfhood, belonging and relation, shaped through lived experience and attentive looking. What began as a form of critical autobiography—painting myself within architectural and historical spaces to examine how colonial structures continue to shape identity—gradually shifted toward a softer, relational mode of image-making. This transition did not diminish the political concerns of the work; rather, it reframed them through intimacy, interdependence and everyday life.

The introduction of my cat as co-subject marked a significant shift in how I locate the self. Drawing on Berger and Haraway, I have come to understand this relationship not as symbolic substitution, but as a shared world. Through this companionship I have become more grounded in the quiet mutuality of daily care. This shift was mirrored materially in paint: my palette expanded, light returned, and the surfaces of the work began to hold warmth rather than only tension.

Throughout this process, I have learned that painting is not simply a tool for representation, but a mode of thinking—slow, layered, and reflective. It enables me to sit with uncertainty, to observe and to transform. As I move forward, I aim to continue developing a practice that focus on my cat as main subject, and to discover relational presence together. Recognising that the self is always formed with others—human, animal, and place. In this way, the work remains open for unfolding, attentive, and ongoing.

Bibliography

Ahmed, S. et al. (2020) Uprootings. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Arjerman, M. (2025) Painting: Michaelajerman.com: England |, My Site 1. Available at: https://www.michaelajerman.com/ (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

ART Walkway (2025) The painter’s dilemma: Light, color, and emotion, ART Walkway. Available at: https://www.artwalkway.com/painters-dilemma-light-color-emotion/#:~:text=When%20you%20move%20from%20a,the%20light%20infuse%20the%20scene. (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

Artsy (2025a) Pierre Bonnard | Le chat blanc (the white cat) (1894) | artsy, Artsy. Available at: https://www.artsy.net/artwork/pierre-bonnard-le-chat-blanc-the-white-cat (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

Artsy (2025b) Pierre Bonnard | The work table (1926-1937) | artsy, Artsy. Available at: https://www.artsy.net/artwork/pierre-bonnard-the-work-table (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

Berger, J. (2000) Why look at animals?, Upenn. Available at: https://web.english.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Berger_LookAnimals.pdf (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

Berger, J. (2000) Why look at animals? London: Penguin.

Britannica Editors Encyclopaedia Britannica’s editors oversee subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge (2025) Treaty of Nanjing, Encyclopædia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Treaty-of-Nanjing (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

British Museum (2025) Architecture | british museum, British Museum. Available at: https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/architecture (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

de Souza, I. (2024) Man’s best friend: David Hockney’s love for dachshunds: MyArtBroker: Article, MyArtBroker. Available at: https://www.myartbroker.com/artist-david-hockney/articles/mans-best-friend-david-hockney-love-for-dachshunds (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

Drucker, J. (2004) The Century of Artists’ book. New York: Granary Books.

Foucault, M. (1982) Technologies of the self: Lectures at University of Vermont in October 1982, Michel Foucault, Info.Available at: https://foucault.info/documents/foucault.technologiesOfSelf.en/ (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

Fox, J. (2023a) ‘Purple The Synthetic Rainbow’, in The World According to Colour: A Cultural History. Penguin, pp. 166–194.

Fox, J. (2023b) The world according to colour: A cultural history. London: Penguin Books.

Gogasian (2018) Anselm Kiefer: Transition from cool to warm, west 21st street, New York, May 5–September 1, 2017, Gagosian. Available at: https://gagosian.com/exhibitions/2017/anselm-kiefer-transition-from-cool-to-warm/ (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

Griffiths, M. (2003) Feminisms and the self: The web of identity. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

Haraway, D.J. (2020) The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, people, and significant otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Hirst, A. and Humphreys, M. (2023) Finding ourselves in space: Identity and Spatiality, figshare. Available at: https://aru.figshare.com/articles/chapter/Finding_Ourselves_in_Space_Identity_and_Spatiality/23761962?file=42197559 (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

Howey, B. (2009a) Critical Autobiography and Painting Practice, University of Huddersfield. Available at: https://files.core.ac.uk/download/pdf/58252.pdf (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

Howey, B. (2009b) Critical Autobiography and Painting Practice, University of Huddersfield. Available at: http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/4966/ (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

Jarbouai, L. (2024) Cats. Paris: GrandPalais RmnÉditions : Éditions du Museé d’Orsay et du Museé de l’Orangerie.

O’Doherty, B. (2010) Inside the White Cube: The ideology of the gallery space. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Perec, G. and Sturrock, J. (2011) Species of spaces and other pieces Georges Perec ; edited and translated by John Sturrock. Johanneshov: TPB.

Perryman, L. (2021) ‘Psychology of Colour’, in The Colour Bible: The Definitive Guide to Colour in Art and Design. UK: An Hachette Company, pp. 34–39.

Rizzi, J. (2019) Pierre Bonnard. London: Tate Publishing.

Sawa, D.B. (2025) Michael Ajerman: ‘I found my reason to keep doing this’. Available at: https://daleberningsawa.substack.com/p/how-a-cat-called-grendel-brought (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

Schjeldahl, P. (2023) 1982: Anselm Kiefer’s Innenraum, Artforum. Available at: https://www.artforum.com/columns/1982-anselm-kiefers-innenraum-165850/ (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

Sothebys Editor (2025) Nicole Eisenman: Close to the edge, Sothebys.com. Available at: https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2019/contemporary-art-evening-auction-l19024/lot.1.html (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

Tate (2025) ‘the window’, Pierre Bonnard, 1925, Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/bonnard-the-window-n04494 (Accessed: 01 November 2025).

Uexküll, J. von and O’Neil, J.D. (2013) A foray into the worlds of animals and humans: With a theory of meaning. S.l.: University of Minnesota Press.

Vitale, K.R., Behnke, A.C. and Udell, M.A.R. (2019) ‘Attachment bonds between domestic cats and humans’, Current Biology, 29(18). doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.08.036.